0.1 Understanding the Power of Frames

The focus in this section is on the key principles around frames and reframing to build a good understanding of why it is so challenging for people to change their minds once they have committed to a frame on a particular issue, especially one where there is a lot of emotional investment. In addition, we provide an overview of how dominant frames are built in public debates/the media and so, outline the challenge for campaigners. Throughout, we draw on lots of thinking from different disciplines and real-life campaign practice.

Starting with our definition:

Breaking down the elements of the definition and implications for campaigners:

Frames are the stories that become part of our common sense.

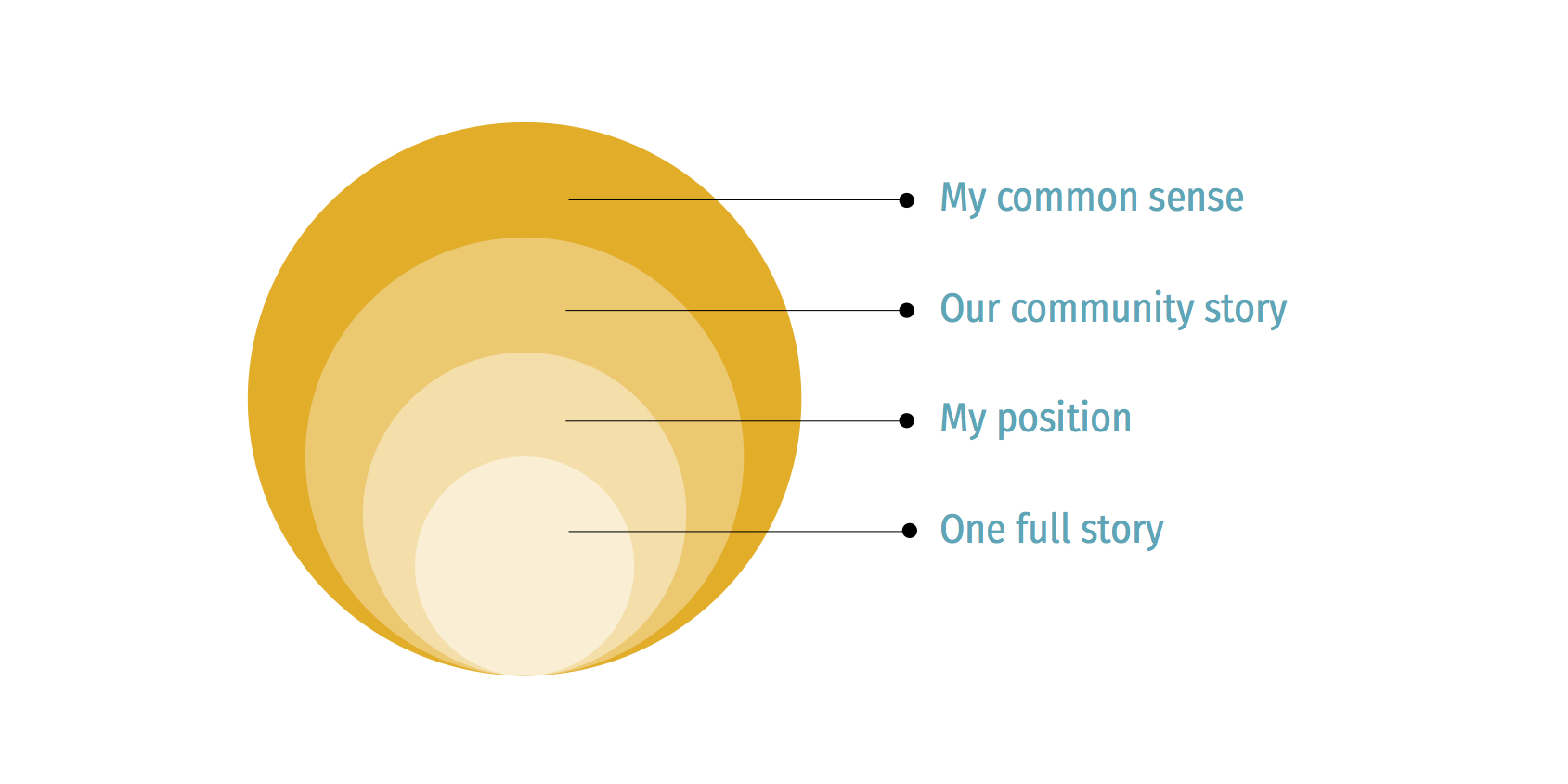

The stories around political issues become powerful through a process of socialisation starting from one explanation on an issue to becoming an identity marker for a particular tribe and eventually, a kind of group common sense. In this evolution, there are four key aspects of frames that are important to understand:

- One full story/narrative - Put simply, frames are stories we use to understand complex and challenging issues in life like migration or climate change. A frame is a full story or narrative that usually covers the nature of the problem, what’s causing it, who the good guys are, who is to blame and what the solutions are. Of course, it is just one story in many possible ways of interpreting and evaluating an issue and in choosing one story, we focus our attention on some areas/concerns and ignore others2

.

- My issue explanation/position - When a new issue becomes part of the public discussion, we tune into mainstream and social media, talk it though with friends and normally guided by our values and political affiliations, we adopt a certain position or frame on the issue. The nature of the stories we choose to adopt is key as they “often determine who deserves our solidarity or our scorn, our compassion or our contempt, our fear or fealty”3

.

- Our community story – Through the process of committing to a single frame we mostly align with the views of our political tribe, make it our go-to understanding on the issue and over time, these frames also become highly valued stories in our political community, further cementing our attachment to the frame to the point of arguably becoming a marker of our in-group identity.

- My common sense – Over a longer time period, these stories become part of our political backbone to the point they actually become part of our ‘cognitive unconscious’4 , or put more simply, our ‘common sense’. This is why they are so easily triggered by a picture, a word or phrase, a metaphor or story5 .

Figure 1: the evolving power of frames thought socialisation

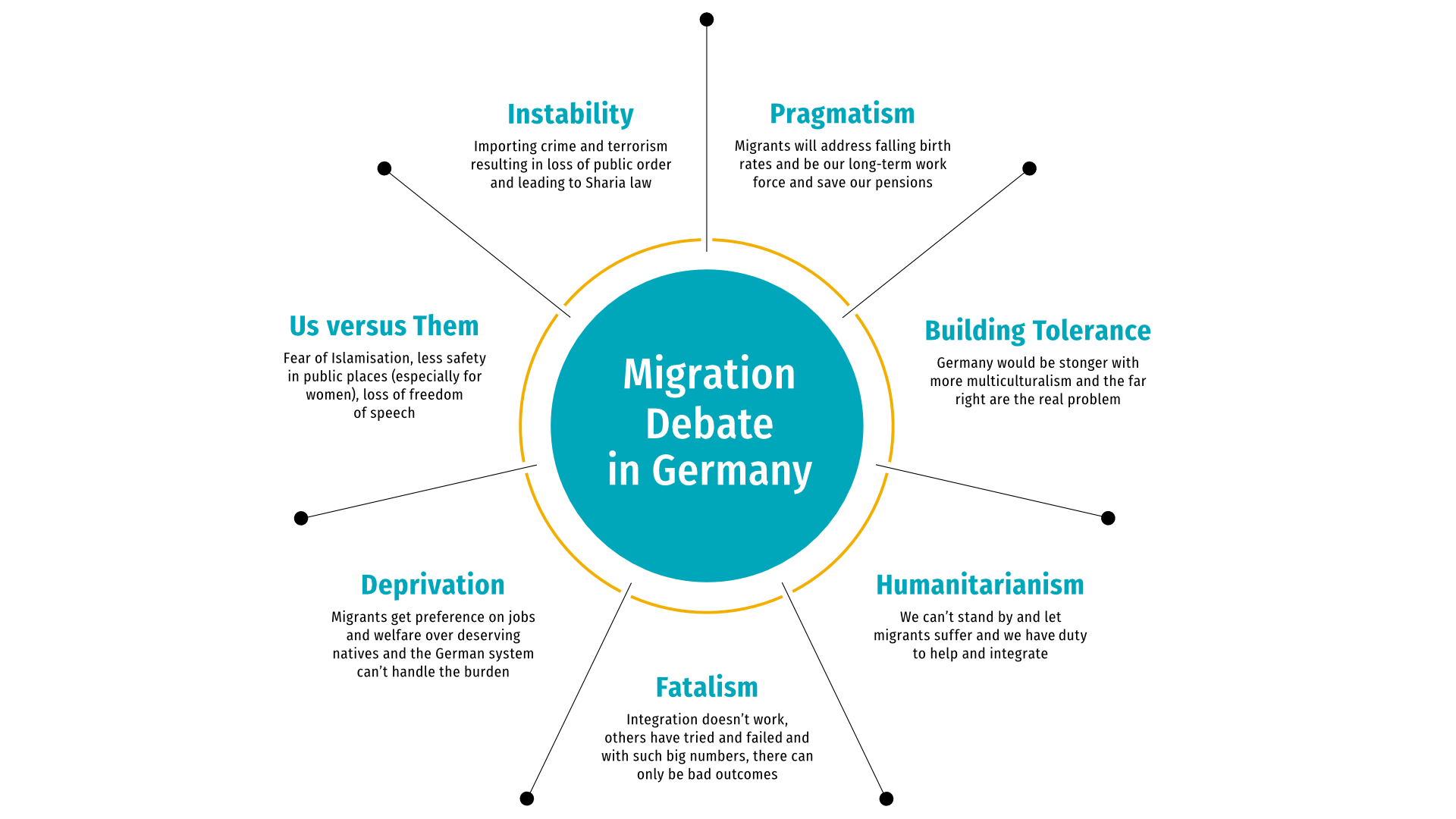

To illustrate the current frames in the migration debate in Germany from across the spectrum, we commissioned a social media analysis6

and based on our analysis, we identified the following seven frames to be the most prevalent:

People are much more frame-driven than fact-driven.

One of our current favourite and most illustrative explanations of the framing effect is that employing this approach is a form of “cultural acupuncture”7 . For example, the UK Prime Minister Cameron’s use of the word “swarm” of migrants in 2015 needed no other explanation to trigger a whole set of negative connotations. For the campaigner, it is key to understand how bonded we are to these stories and indeed, as “pattern seeking, storytelling animals”, that we cannot stand any absence of meaning established in these patterns8 . It is well recognized that humans are much more frame-driven than fact-driven and this explains why fact-driven, myth busting approaches don’t often work so well and also why campaigners get such emotional responses when challenging existing frames. On the flip side, if we can make an appeal to ‘common sense’ that also creates a crack in the existing story (triggering cognitive dissonance), then we really do have an opportunity to change the story. This is the intention of the campaigning approach outlined in the guidelines.

The challenge of dominant frames, mainstreaming and partisan bubbles

Frames that are ‘sticky’/resonant, coherent and accessible, brought to us from trusted sources and repeated a lot have a very good chance of becoming a competitor to existing frames or eventually even becoming the dominant story on a political issue9

. According to the literature, a single dominant frame in the media will often lead the debate and set the public agenda10

and once it becomes established, it becomes very difficult to get air time for any new stories that do not fit this line11

. The media play a large role in the normalisation or mainstreaming of dominant frames, and they often do this in a way which produces a “tidy media narrative” which oversimplifies and overdramatises such political stories12

, especially in tabloids that are an important channel in reaching the movable middle. As mentioned above, from a policy perspective, once established this frame will set the boundaries of “acceptable” policy options13

. In this populist era, frames of cultural invasion, the perceived threat of Islam and loss of control/security are becoming more mainstream in the migration debate and setting the boundaries of the migration agenda.

Our natural emotional attachment to resolve reality in the values and frames of our political brothers has been very much facilitated recently by social media that allows us to construct a world literally of all the opinions we ‘like’. After many recent election results, social media has also been seen to increase partisanship, leading to significant reflections on the challenges of dealing with bubbles, silos and echo chambers in a democratic debate. The internet has opened virtually free access to all kinds of data, as well as distraction. In driving partisanship, the space has now become the ‘attention economy’, where click-bait headlines driven by outrage frames compete to get us onto their page to increase their advertising revenue and also build our emotional attachment to remain in the online tribe14

. Further, in the information overload of the attention economy, “symbols can succeed over substance” and the shorthand of meme culture rather than considered analysis becomes a significant driver of political debates15

. These processes of the production and reproduction of competing frames in a hyper-partisan world is a significant rationale for this toolkit and an emotionally smart narrative change campaign approach.

<< 0.0 Guidelines Intro - 1.0 >>

- 1Drawing on core sources, e.g. Lakoff, George (2014). Don't think of an elephant!: know your values and frame the debate : the essential guide for progressives. 2nd Edition. White River Junction, Vt, Chelsea Green Pub. Co. & FrameWorks Institute (2009) Changing the Public Conversation on Social Problems: A Beginner’s Guide to Strategic Frame Analysis, E-Workshop & Kanneman, Daniel (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books.

- 2Entman, Robert M. (2003) Cascading Activation: Contesting the White House's Frame After 9/11, Political Communication, 20:4, 415-432.

- 3Narrative Initiative (2017) Towards New Gravity: Charting a course for the Narratives Initiative.

- 4Lakoff, George (2014). Don't think of an elephant!: know your values and frame the debate. 2nd Edition. White River Junction, Vt, Chelsea Green Pub. Co.

- 5Lakoff, George (2014). Don't think of an elephant!: know your values and frame the debate. 2nd Edition. White River Junction, Vt, Chelsea Green Pub. Co. & FrameWorks Institute (2009) Changing the Public Conversation on Social Problems: A Beginner’s Guide to Strategic Frame Analysis, E-Workshop & Kanneman, Daniel (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books.

- 6commissioned from Bakamo Social

- 7Narrative Initiative (2017) Towards New Gravity: Charting a course for the Narratives Initiative.

- 8Allenby & Gerreau quoted in Narrative Initiative (2017) Towards New Gravity: Charting a course for the Narratives Initiative.

- 9Entman, Robert M. (2003) Cascading Activation: Contesting the White House's Frame After 9/11, Political Communication, 20:4, 415-432. & Scheufele, Dietram A (1999) ‘Framing as a theory of Media Effects’ in Journal of Communication, Winter 1999, p.103-122. & Sunstein, Cass R. & Adrian Vermeule (2008) Conspiracy Theories. Harvard Public Law Working Paper No. 08-03.

- 10Kanneman, Daniel (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books & Nyhan, Brendan & Jason Reifler (2010) When Corrections Fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. & Waller, R. L., & Conaway, R. N. (2011). Framing and counterframing the issue of corporate social responsibility the communication strategies of nikebiz.com. Journal of Business Communication, 48, 83-106

- 11Entman, Robert M. (2003) Cascading Activation: Contesting the White House's Frame After 9/11, Political Communication, 20:4, 415-432. & FrameWorks Institute (2009) Changing the Public Conversation on Social Problems: A Beginner’s Guide to Strategic Frame Analysis, E-Workshop

- 12Lakoff, George (2014). Don't think of an elephant!: know your values and frame the debate. 2nd Edition. White River Junction, Vt, Chelsea Green Pub. Co. & Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Supplement, 13, 106-131.

- 13Scholten, P. & F. Van Nispen (2008) “Building Bridges Across Frames? A Meta-Evaluation of Dutch Integration Policy”. Journal of Public Policy 28/2, p.181-205.

- 14Williams, James (2017) Stand Out of Our Light: Freedom and Persuasion in the Attention Economy

- 15Narrative Initiative (2017) Towards New Gravity: Charting a course for the Narratives Initiative.