Presence instead of press release: The importance of media strategies for narrative change campaigns (by Alice Lanzke)

At the CLAIM Alliance networking meeting, Corey Saylor gave a valuable keynote on the importance of media for strategic communications. Alice Lanzke summarises Corey's central statements, which guide the work of ICPA's new Media Hub.

Every successful narrative change campaign needs publicity. And to a large extent, this still includes classic mass media. For it is above all the target groups of the moveable middle that obtain a considerable part of their information from daily newspapers, magazines, television or radio. This makes it all the more important for activists and campaigners to include them in the planning of their strategic communications.

The central role of media work in this context was illustrated by Corey Saylor's keynote at the networking meeting of the CLAIM Alliance, which took place in Berlin at the beginning of October 2020. Corey is "Deputy Director of Campaigns" of the US organisation "ReThink Media"1 , whose approach is based on the following conviction:

Media and communications are thus not only essential for campaign work, but for movement building in general. Accordingly, "ReThink Media" supports non-profit organisations through media training, public opinion evaluations, including through focus groups, and training on message development and cohesion. What this means - also and especially for smaller organisations - is impressively illustrated by a case study presented by Corey: ReThink Media was contacted by one of its partner organisations. The organisation represented a young man whose mother suffered from a fatal brain disease in Iran. A US surgeon from Louisville had agreed to perform the life-saving operation free of charge - however, the so-called "Muslim Ban" prohibited the woman's entry into the USA at the time3 . "ReThink Media" subsequently considered who would need to be approached to secure an exemption. "And that was the Department of State and specifically the people who worked there," says Corey. A traditional approach would have involved a broad media campaign to draw attention to the story: "But that approach wouldn't necessarily have reached the people it needed to." In particular, those people probably wouldn't have listened to activists, but they might have listened to journalists.

Accordingly, "ReThink Media" set out to place the story in Louisville's local newspaper: Unlike national media, there was more interest in publishing an article here because it was about the local hospital and one of the doctors there. In the next step, ReThink Media asked its partner organisations to tweet the article specifically to people from the Department of State and to reporters who cover the Department. In fact, within a few hours, the story generated widespread attention, which eventually led to an exemption being granted for the sick woman.

-

Media legitimacy is still central to the success of many campaign efforts. Certain target groups cannot be addressed if traditional media are left out. Accordingly, it is important to think about those media at the beginning of any campaign and to include them at the appropriate time. This requires strategic planning and preparation. In this context, an approach that does not see the media as "enemies" of one's cause, but rather as conscious or unconscious allies, is promising. In this case, the report in the local newspaper gave the whole story confirmation and legitimacy that a direct call by the activists - at least for the target group of Department of State employees - would not have received. That validation and legitimacy then built leverage and ultimately pressure on those protagonists who were crucial to the success of the campaign. In addition, a narrative was translated into a media story, namely the case of the doctor ("hero" character) who offers to treat the terminally ill woman for free.

-

Many activists aim for national coverage with their media strategy. But this is not always possible and not always necessary, as Corey's example shows. The local framework can often be much more effective for campaigners: The local newspaper in the example described had an active interest in reporting on the doctor because he is part of the local community. Accordingly, it was easier for the activists to get coverage and, through this channel, support, which achieved impact in the local space.

-

However, the points made here do not mean that successful campaigns should focus mainly on traditional media - on the contrary, Corey's example shows how important it is nowadays to think of traditional media and social media as intertwined in one's media strategy and to act accordingly. By calling on the network to tweet the local article to specific targets (people from the Department of State as well as reporters covering the Department), the issue received a much more focused response, which ultimately led to the activists' success.

All in all, the example of Corey Saylor and the lessons we can learn from it show that not only campaign planning as a whole, but also the media strategy(s) within this planning must be included early and intensively. Media strategy is not about writing a particularly successful press release or being featured as a topic in the "Tagesschau". Rather, it is about getting your message(s) into the media that is consumed by the people who are crucial to the success of a campaign - in this way, the media strategy creates leverage for the overall campaign goal.

The message that is carried in the media does not necessarily have to be the message that is most convincing to activists themselves - as long as it still fits with their own values. In Corey's example, this was easy because the message touched on the value of humanity, a value that most people can probably agree on. But this is not the case with all campaigns. Moreover, Corey points out, political victories are rarely won by a single person or organisation, but by the unification of many different groups, in other words, by building a movement.

Fewer messages, more reporting

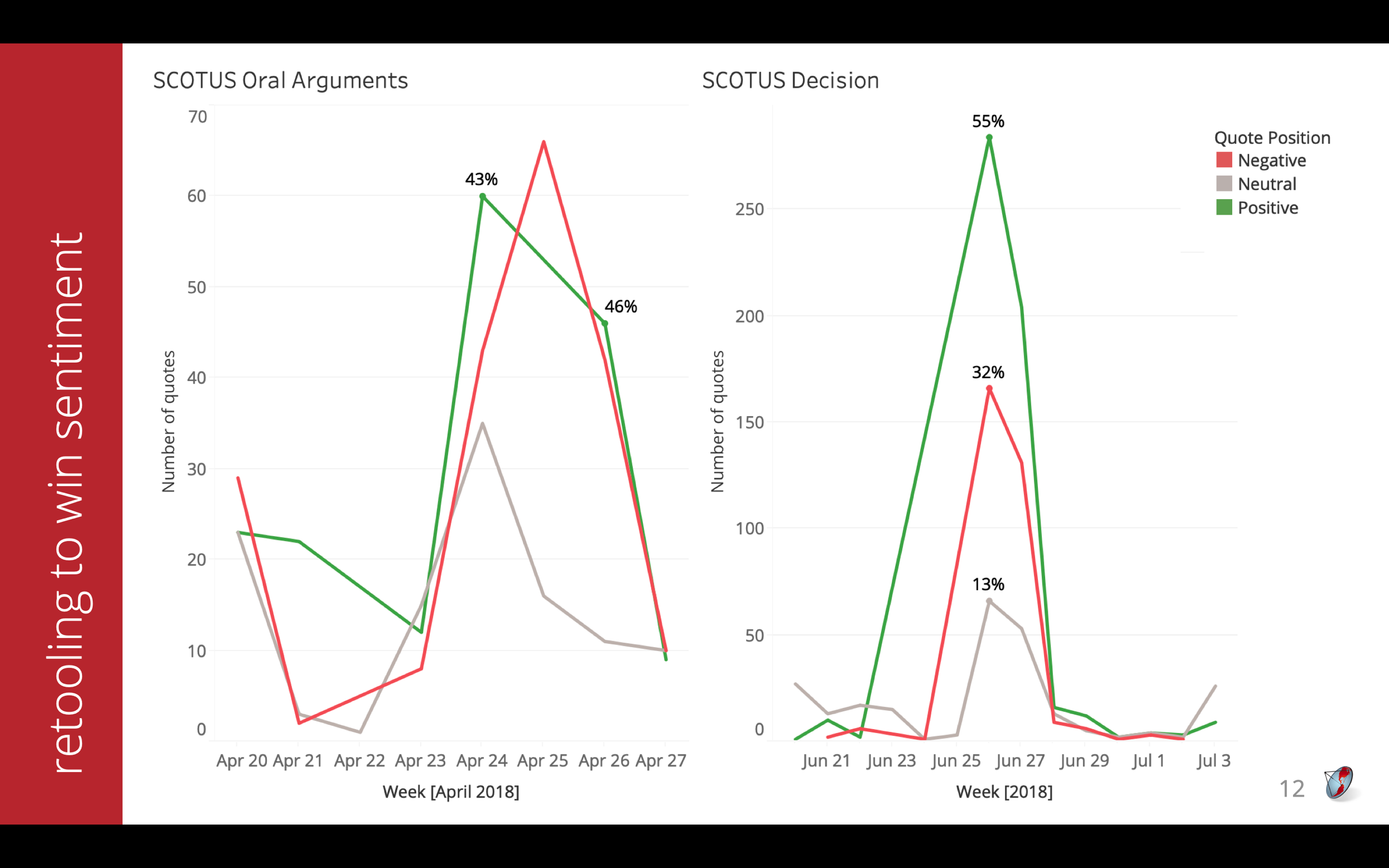

Meanwhile, in these same movements, it is central to develop a coherent narrative or unified "messaging moment" that can be conveyed through the media. "It's not about a TV interview - it's about building a narrative that is perceived by many people in many different ways," Corey explains in his second case study: The Supreme Court of the United States had to decide at that time whether the establishment of the "Muslim Ban" was legal - as a result, there were regular demonstrations of various groups and activists in front of the building. However, as Corey observed, there was initially a confusion of posters and messages. This confusion was directly reflected in the media coverage. Corey reports that the media analysis by "ReThink Media" revealed nine different messages that were reported on. All of these messages, while important and correct, did not add up to a coherent and powerful moment, especially given the fact that the proponents of the Muslim Ban focused on a small number of messages that were subsequently all the more effective and picked up by the media.

This experience made it clear to "ReThink Media" that a coalition of different organisations with different interests is needed, which nevertheless represent a common narrative that can be translated into media stories. Because, according to Corey, a narrative resonates with media consumers. In order to achieve sustainable presence and strength, discipline in message dissemination is necessary.

Over the next few months, Corey accordingly held dozens of talks with activists to get everyone on the same "messaging page" - with success: during the renewed demonstrations in front of the Supreme Court, but also at many airports around the country and in front of the White House, the activists' demands dominated the media coverage and thus the public discussion, in which the number of different messages was reduced to four.

In the end, on 26 June 2018, the court declared the "Muslim Ban" to be legal; however, the activists' narrative had nevertheless successfully prevailed: even the opponents of the protest subsequently repeatedly spoke of it as "NOT a Muslim Ban" - and in this way used the very term they wanted to avoid because of its chilling effect. When US Democrat Joseph Biden replaced Trump, he overturned the decree on his first day in office. Of course, it is impossible to say with certainty what motivated Biden to do so, but the fact that it was one of his first moves is perhaps also a result of the media coverage gained by the activists who fought against the Muslim Ban, proving that "coherence leads to coverage".

Quando si gioca in rete, la sicurezza deve essere sempre al primo posto per evitare spiacevoli sorprese. Affidarsi ai casinò online legali in Italia con soldi veri assicura che ogni sessione sia protetta dalle normative ADM, che vigilano sulla correttezza degli algoritmi e sulla tutela dei fondi degli utenti. Solo operando su siti autorizzati si ha la certezza che le vincite siano pagate regolarmente e che i dati personali siano trattati con i più alti standard di crittografia.

It is clear that building such a movement takes preparation and time. Most importantly, Corey says, activists should remember that communication is not just about writing a press release. Rather, communication is a "consciously crafted narrative that takes into account the audience you need to reach". Central to this is what moves this audience, not what would move one oneself. On the other hand, communication means approaching people and building a movement around a political goal, even if one does not agree 100 per cent.

Key lessons

What makes Corey's keynote so valuable for ICPA's work, but also for activists and campaigners in general, are the key recommendations that can be drawn from it for your own media work4 : Know your audience and build a diverse network with effective (but not restrictive) discipline in message dissemination. Above all, be aware that winning the narrative as well as the media space needs long-term commitment - so stay persistent and persevering!

Alice is a freelance journalist who has been working in the media since 2005. In addition, she is involved with various NGOs, most recently and still today with the Neue Deutsche Medienmacher*innen as a trainer, lecturer and consultant. Alice has been part of the Narrative Change Lab since its inception and now leads the Media Hub of the ICPA Strategic Communications Incubator, which supports the RESET project .

- 1https://rethinkmedia.org

- 2In the original: "Movements most powerfully come together and capture the public imagination where they intersect with their audience-in the media". (Source: https://rethinkmedia.org/our-work)

- 3Executive Order 13769, also known as the "Muslim Ban", describes a decree by then US President Donald Trump that banned citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the US for 90 days, refugees for 120 days and refugees from Syria permanently. Read more at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Executive_Order_13769

- 4Further suggestions are provided by the case studies in the ICPA toolkit: http://www.narrativechange.org/toolkit/campaign-cases